A couple of years back, just after I embarked on an MFA program in fiction at George Mason University, a friend gave me the book So Many Books, So Little Time: A Year of Passionate Reading. In a twist of slightly cruel irony, she also gave me a second book with a similar title: So Many Books: Reading and Publishing in an Age of Abundance. I read, enjoyed and admired the second one, but never found time for the first, which still sits unread. Turns out my friend — and these authors — had proven their own starting point: So many books, and rarely enough time.

A couple of years back, just after I embarked on an MFA program in fiction at George Mason University, a friend gave me the book So Many Books, So Little Time: A Year of Passionate Reading. In a twist of slightly cruel irony, she also gave me a second book with a similar title: So Many Books: Reading and Publishing in an Age of Abundance. I read, enjoyed and admired the second one, but never found time for the first, which still sits unread. Turns out my friend — and these authors — had proven their own starting point: So many books, and rarely enough time.

There is never a lack of books that I want to read — piled on my desk or by my bedside table or on the shelves in my office — and this is far from a unique complaint. Few of my friends can keep up with their reading “to-do” list. And since many of us are writers as well, there’s a balance as well between time spent reading and time spent writing — not an easy balance at that.

In my work as a professor at George Mason University, I’m re-reading Madison Smartt Bell’s Narrative Design for the fiction workshops I teach and Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point for a pair of advanced composition classes. In my work as a freelance book critic, I’ve recently read a pair of mystery/thriller titles for the Washington Post (deadlines met!); I’m delving into the novels of John Hart for the North Carolina Literary Review (one of which I reviewed for the Post last year); and I’m browsing through both a quaint little title called Ghost Cats of the South and the second edition of a restaurant guide called Interstate Eateries for my work as a contributing editor at Metro Magazine in North Carolina.

In my work as a professor at George Mason University, I’m re-reading Madison Smartt Bell’s Narrative Design for the fiction workshops I teach and Malcolm Gladwell’s The Tipping Point for a pair of advanced composition classes. In my work as a freelance book critic, I’ve recently read a pair of mystery/thriller titles for the Washington Post (deadlines met!); I’m delving into the novels of John Hart for the North Carolina Literary Review (one of which I reviewed for the Post last year); and I’m browsing through both a quaint little title called Ghost Cats of the South and the second edition of a restaurant guide called Interstate Eateries for my work as a contributing editor at Metro Magazine in North Carolina.

And yet, I still I find myself planning ahead for the books I want to read. Reading for pay can’t replace reading for pleasure — and reading for pleasure has, of course, more abstract profits of its own. Last week, I managed to track down an already increasingly hard-to-find copy of the new American edition of B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, and this week received from Amazon both Brian Brodeur’s new poetry collection, Other Latitudes, and Pagan Kennedy’s new essay collection,The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories. Last night, I read aloud to my fiancée Tara a couple of stories from a new volume of William Maxwell’s writings from Library of America; I’d just gotten it in the mail on Thursday.

And yet, I still I find myself planning ahead for the books I want to read. Reading for pay can’t replace reading for pleasure — and reading for pleasure has, of course, more abstract profits of its own. Last week, I managed to track down an already increasingly hard-to-find copy of the new American edition of B.S. Johnson’s The Unfortunates, and this week received from Amazon both Brian Brodeur’s new poetry collection, Other Latitudes, and Pagan Kennedy’s new essay collection,The Dangerous Joy of Dr. Sex and Other True Stories. Last night, I read aloud to my fiancée Tara a couple of stories from a new volume of William Maxwell’s writings from Library of America; I’d just gotten it in the mail on Thursday.

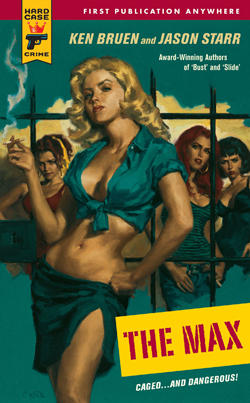

True to my first passions for reading — mysteries — I also ordered at the end of last month an old Ross Macdonald omnibus, Archer at Large, gathering three of his best: The Doomsters, The Zebra-Striped Hearse, and The Instant Enemy, and I’m a subscriber to the Hard Case Crime series, too. Even though the Hard Case Crime titles are ultimately a little hit-and-miss, the arrival of a new one in the mail (the latest shown here) is always cause for a little excitement — and then for a small let-down as I realize that I simply can’t keep up with reading them each month. And so the latest is added to the end of the series, waiting until I can find some free time to sit back and enjoy it or another of its brothers and sisters up their on the shelf.

True to my first passions for reading — mysteries — I also ordered at the end of last month an old Ross Macdonald omnibus, Archer at Large, gathering three of his best: The Doomsters, The Zebra-Striped Hearse, and The Instant Enemy, and I’m a subscriber to the Hard Case Crime series, too. Even though the Hard Case Crime titles are ultimately a little hit-and-miss, the arrival of a new one in the mail (the latest shown here) is always cause for a little excitement — and then for a small let-down as I realize that I simply can’t keep up with reading them each month. And so the latest is added to the end of the series, waiting until I can find some free time to sit back and enjoy it or another of its brothers and sisters up their on the shelf.

And that’s the point to some degree: As passionate we as readers might be, we live in an embarrassment of riches, and likely already have an embarrassing backlog of books on our own shelves that we’d brought into our homes with the very best of intentions — an honored guest, one we’re excited to welcome into our company — and then quickly neglected as we went about household chores, or watched TV, or struggled to get ready for the next day at work or to wind down after a long day on the job, or (in the case of me, my fiance, and many of my friends) to try to write books of our own to add to that abundance (and hopefully not disappear themselves in the midst of it all).

Gabriel Zaid’s So Many Books — the title I referred to in my opening, the one that I actually did read — offers up a sobering statistic. Imagining a “universal library system” which includes every title ever published in the history of mankind (or at least up until 2003, when Zaid’s book was published), he imagines what it would take for a person to read those more than 50,000,000 titles. “Suppose,” he writes,

that every human being is allowed to collect a salary for dedicating himself solely to the reading of books; that under these conditions, each reader is able to read four books a week, two hundred a year, ten-thousand in a half-century. It would be as nothing. If not a single book were published from this moment on, it would still take 250,000 years for us to acquaint ourselves with those books already written. Simply reading a list of them (author and title) would take some fifteen years…. Our simple physical limitations make it impossible for us to read 99.9 percent of the books that are written.

And yet we readers find our curiosity arising almost endlessly, it seems — the desire to read more, to learn more from those other voices and other worlds, or just to escape into them for a little while.

I’m not sure what kind of attention I can give to all the titles I’d like to explore in these postings — again, books that I’m not already writing about in publications out there with a much wider readership than one small blog. But I hope to make this a place to record some thoughts and impressions that might not have another outlet, and even if these posts don’t find their own readership (so many blogs, so little time!), at least they’ll provide a place for me to work out some of my own thoughts about the twinned literary pursuits of reading and writing.

— Art Taylor