I met Sue Grafton only once—so briefly that as I’m writing this, I wonder, to be honest, if it actually happened or if I only thought about it happening. Back in 2011, when Grafton won the Lifetime Achievement Award at Malice Domestic, I attended the closing-day chat with her, and during the excellent interview, I remember wanting to tell her about having taught her debut novel A Is For Alibi in a course at George Mason University. I planned to catch her after the interview, talk to her briefly, offer up my story, and… and I’m not sure whether I actually managed to talk with her or just wanted to so badly that I’ve somehow remembered a brief encounter than never took place. (Sorry for the glimpse into the odd ways my mind works.)

In any case, I want to share that story about Mason now, especially since one of my students from that course reached out to me within a couple of hours after the announcement of Grafton’s death. “Sue Grafton died and I thought about you,” he emailed, and then went on that “the detective fiction course you taught where we read Grafton’s work was one of the highlights of my college career.” It was the first I’d heard from him in years, and yet, as with him, that class was the first thing I thought about when I heard the news that she’d died.

I’ve been very fortunate to have taught many fine, fun courses at Mason and to have worked with so many talented students—students who’ve often felt like friends, often become friends, in fact—but one class has stood out as special above all others.

Fall 2009 brought one of the first survey courses in detective fiction that I taught at Mason—this one with specific focus on hard-boiled detective fiction as social documentary. (You can argue elsewhere about whether the texts I chose all constitute hard-boiled crime fiction.)

This was my first course with 40 students, and the room felt too small for all of us, but something about the energy and interests of the students and the closeness of the rooms combined for a vibrant dynamic. Often the students would kick off discussions of readings even before I got into the classroom; I remember one class meeting—on Dorothy B. Hughes’ In A Lonely Place—where I basically discarded my lesson plan to follow what the students were interested in talking about. I remember too a couple of guys who sat in the back row, rarely contributed to class, but then adopted the names Coffin Ed and Grave Digger on their quizzes after we read Chester Himes’ Cotton Comes to Harlem; one of them emailed me later to say how much he’d enjoyed the reading. And then there was the woman who handed in her final exam and then walked around to my side of the front desk and held our her arms wide for a hug. I hesitated, as you might imagine, and then she explained that she’d never read an entire book before our course—”and now I’ve read seven!”

Reader, I hugged her.

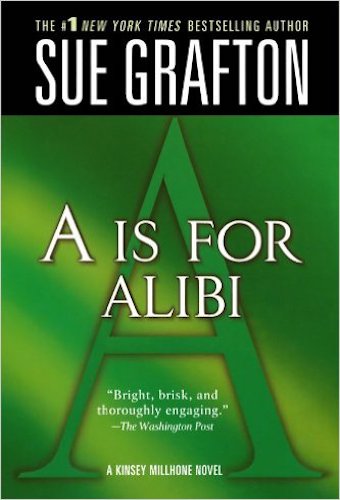

The last text on the syllabus was Grafton’s A Is for Alibi. I meant no offense then—and mean none now—by saying that I wanted to end the course with a lighter read. After Cotton Comes to Harlem, we’d read George Pelecanos’ Hard Revolution—both books dealing with tense and complicated race issues—and Grafton’s book promised, I thought, a bit of relief. That’s not to say that we lacked opportunities for discussion with A Is for Alibi. One the contrary, the book remains one of my favorites to teach. We started by comparing and contrasting Kinsey Millhone to Chandler’s Philip Marlowe and then discussing the debut novels of Grafton, Sara Paretsky, and Marcia Muller in the context of changes in attitudes toward feminism; as Maureen Reddy claimed in “The Feminist Counter-Tradition in Crime,” the 1980s were the decade in which “Feminist literary criticism, feminism as a social movement, and feminist crime novels have grown up together”—in some ways the mainstreaming of second-wave feminism. In many ways, the characters in A Is for Alibi catalogue the various experiences that women (at least white women) might have had in the early 1980s: mother, daughter, single, married, divorced, work-oriented, discriminated against—you could go right down the line, character after character, and find some specific facet of societal expectations about women, their roles, and their responsibilities, and then the challenges to those expectations, the friction and the turmoil of the era.

I wrote “lighter” above, and yet none of that seems “light,” of course. And in fact, the memory I’m working toward is when a couple of the guys in the class—being purposefully provocative, it seemed to me, even mischievously so—started to make some sexist comments about the characters in the book, and a couple of the women two aisles over began to debate with them about their points, a debate that got louder and more animated and then angrier, to the point that I thought one of the women was going to pounce across the desks toward one of the men those two aisles away—literally on her feet and poised to jump.

Somehow, the conversation still remained articulate and productive. This was the course, as I said, where the students—these very students, in fact—were eagerly discussing our reading whether I was there or not. Their conversations got heated from time to time, but only because of how invested the students were in their beliefs, opinions, and arguments. And, ultimately, because of the power of the book they were reading—A Is for Alibi‘s ability to engage, to challenge, to broaden perspectives.

It was exhilarating, frankly, and this was the story that I wanted to tell Grafton at Malice that year—though if I did talk to her at all, I’m sure I just said that I’d taught her book, that the students got a lot out of it, that I appreciated her work generally.

Whether or not I met Sue Grafton may ultimately matter very little. More important than a brief conversation or a quick handshake are the books themselves. Those I remember, and the longer conversations about them, what they brought to readers, and that’s what I was thinking about when the sad news of her death came through.